The protest was a response to an unfortunate advertising campaign by Olivetti Typewriters promoting “brainy” typewriters that were supposed to eliminate the typing errors made by incompetent secretaries. A TV commercial showed a secretary as a vacuous pin-up girl who found that she could attract men by becoming an “Olivetti girl.” This infuriated a group of New York City secretaries, backed by members of the National Organization of Women, which picketed Olivetti’s headquarters at 500 Park Avenue (“Rebel Secretaries,” Time, 20 March 1972).

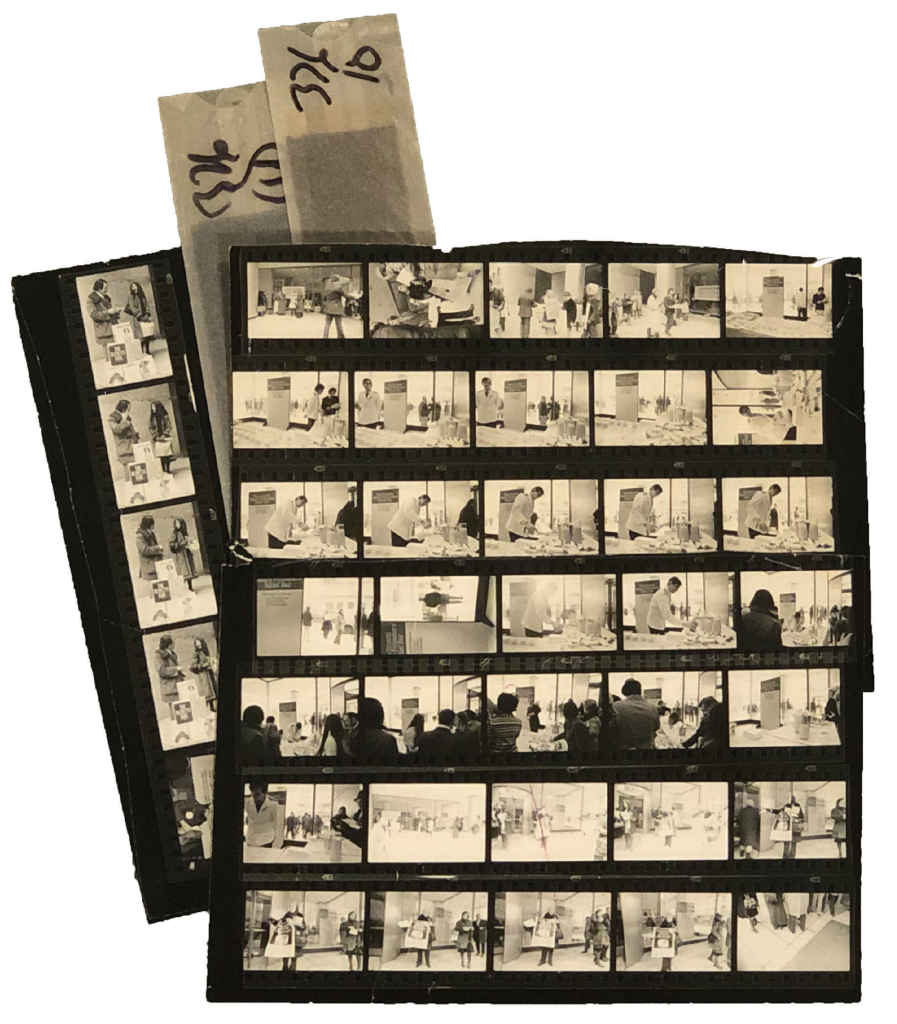

The photographs, shot in black and white by an unknown photographer, show women with protest signs outside the headquarters. Additional photos show a man setting up the “Olivetti Weary Protestors Relief Bar,” where “the liberator” was being served: “one part orange juice, one part Cointreau, one part champagne.”

The Italian typewriter company, founded in 1909, is credited with manufacturing the first programmable desktop computer, the Programma 101, launched at the 1964 World’s Fair.