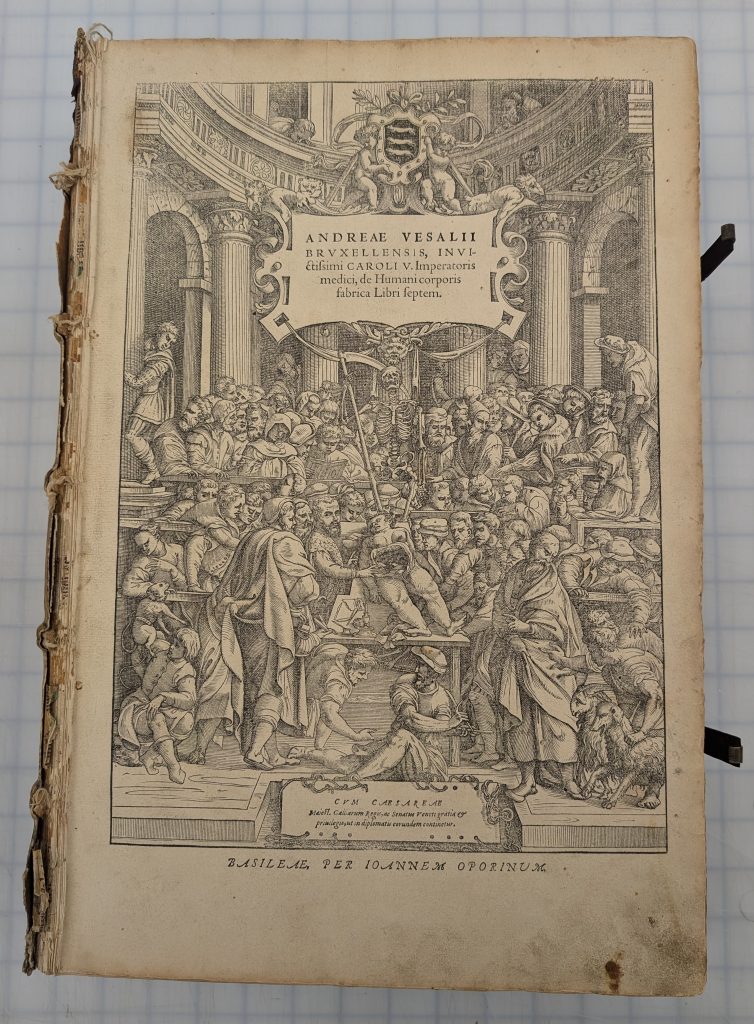

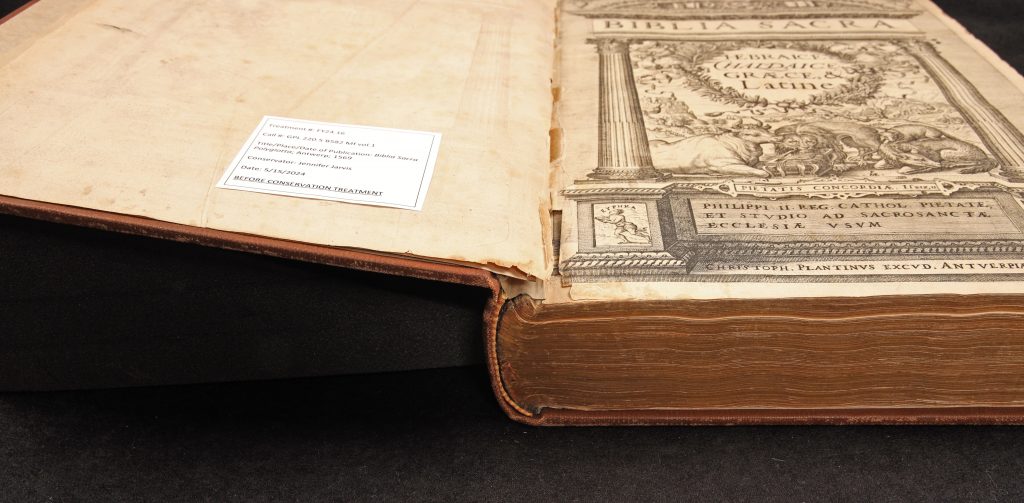

The Plantin Polyglot or Biblia regia constitutes the third large-scale polyglot bible edition in European history, after the famous Complutensian polyglot of 1514–7, and Johns Hopkins’ superb copy of the Genoa polyglot psalter of 1516. Many of the original 1,200 copies were lost in a shipwreck en route to Spain. A handful of copies of the Plantin Polyglot Bible are found today in European and American libraries.

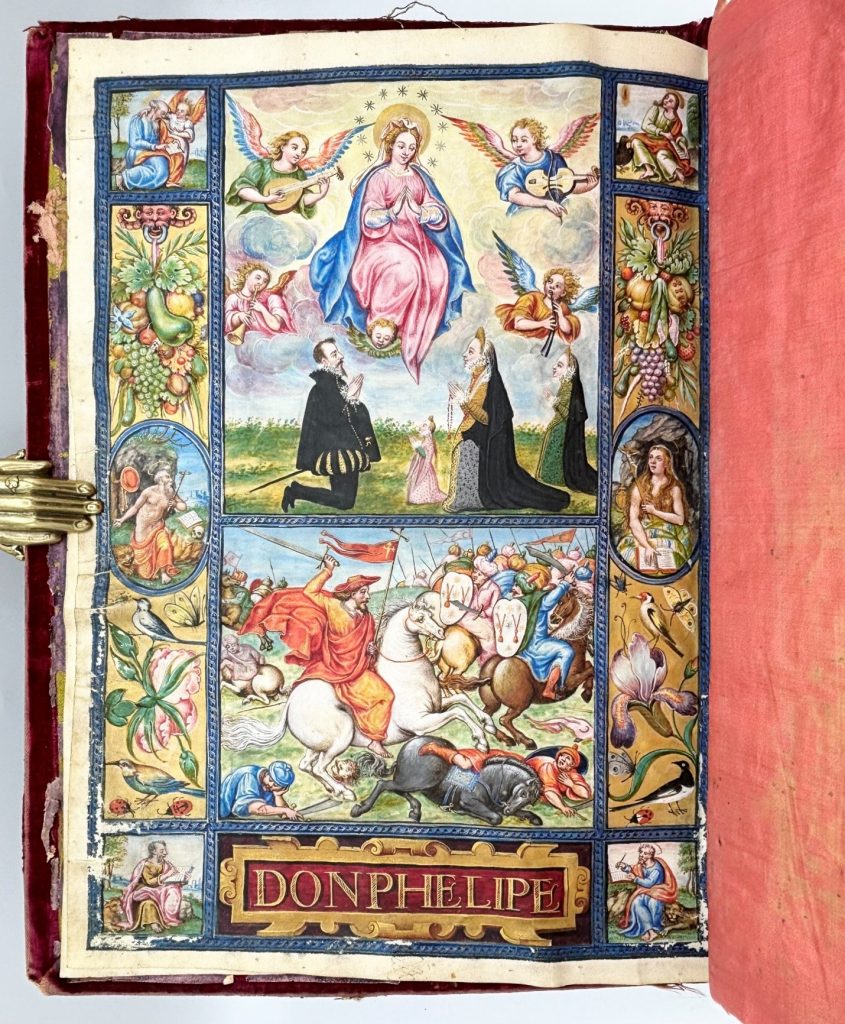

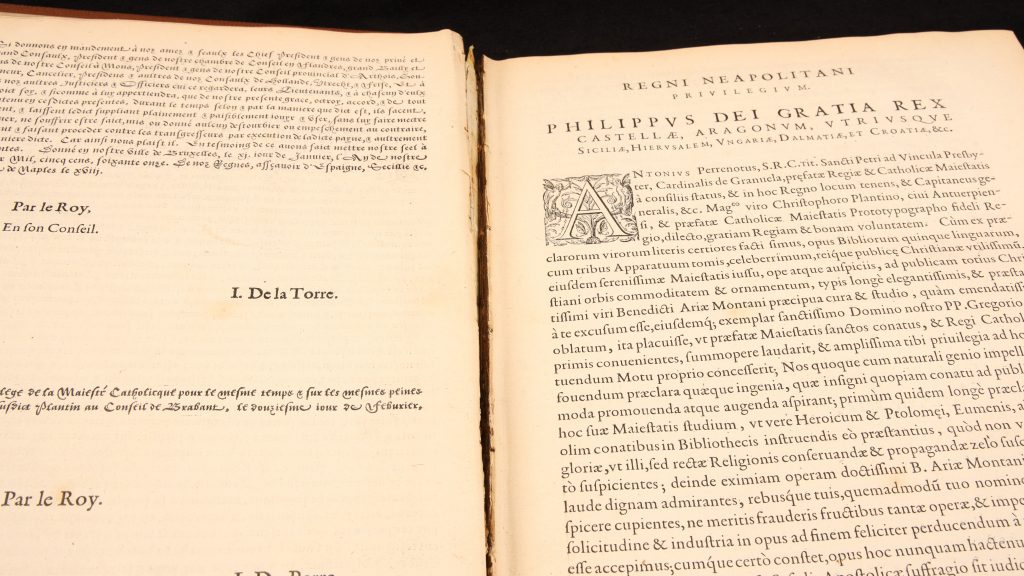

Published in eight volumes between 1569 and 1572 in Antwerp by the leading printer of the northern Renaissance, Christopher Plantin (around 1520–89), this bold project was underwritten directly by King Philip II of Spain. Produced by an international team of linguists, biblical scholars, and more than 40 printers, the Plantin Polyglot is a breathtaking masterpiece both of philology and typography. It is, simply put, one of the most famous books ever printed.

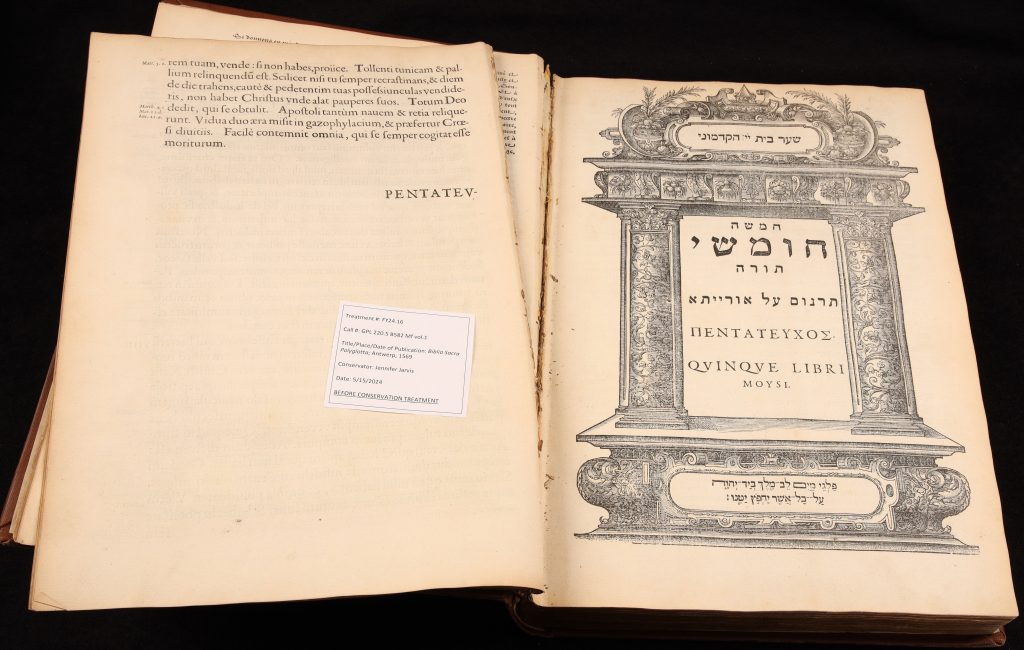

The first volume of Johns Hopkins’ copy, which is used frequently for teaching and scholarship, is in need of conservation treatment. It contains the Pentateuch—the first five books of the Hebrew Bible—in the original Hebrew with parallel translations in Latin and Greek as well as an Aramaic commentary (targum) below the main texts.

Conservation Treatment

Remove from current binding, mend and guard all spine folds and other tears/losses in paper, re-sew, and re-bind using conservation-grade materials and structure.

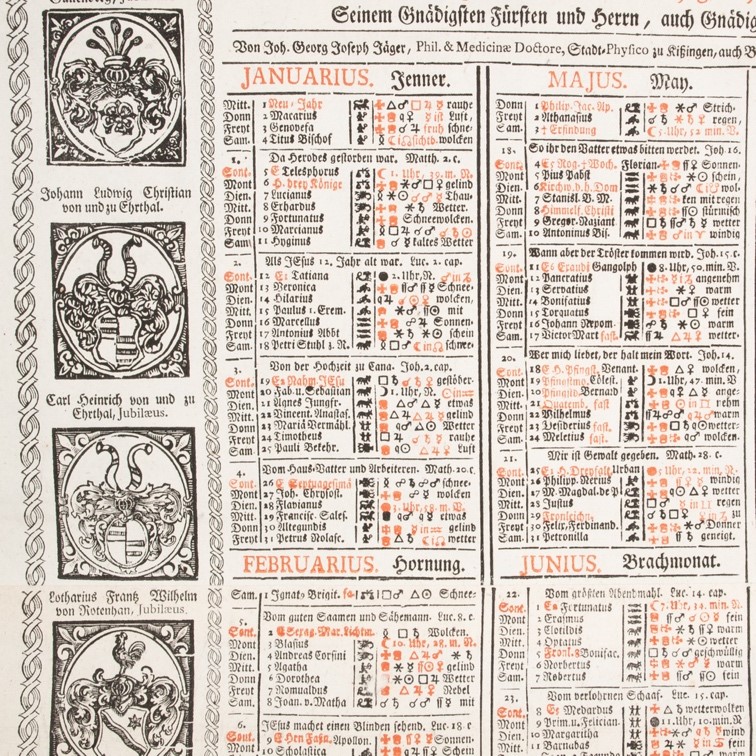

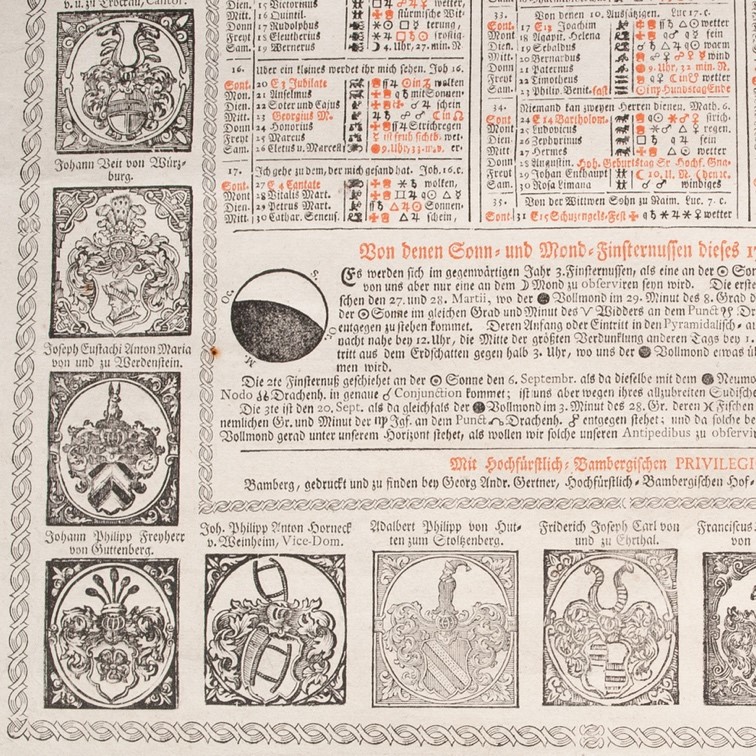

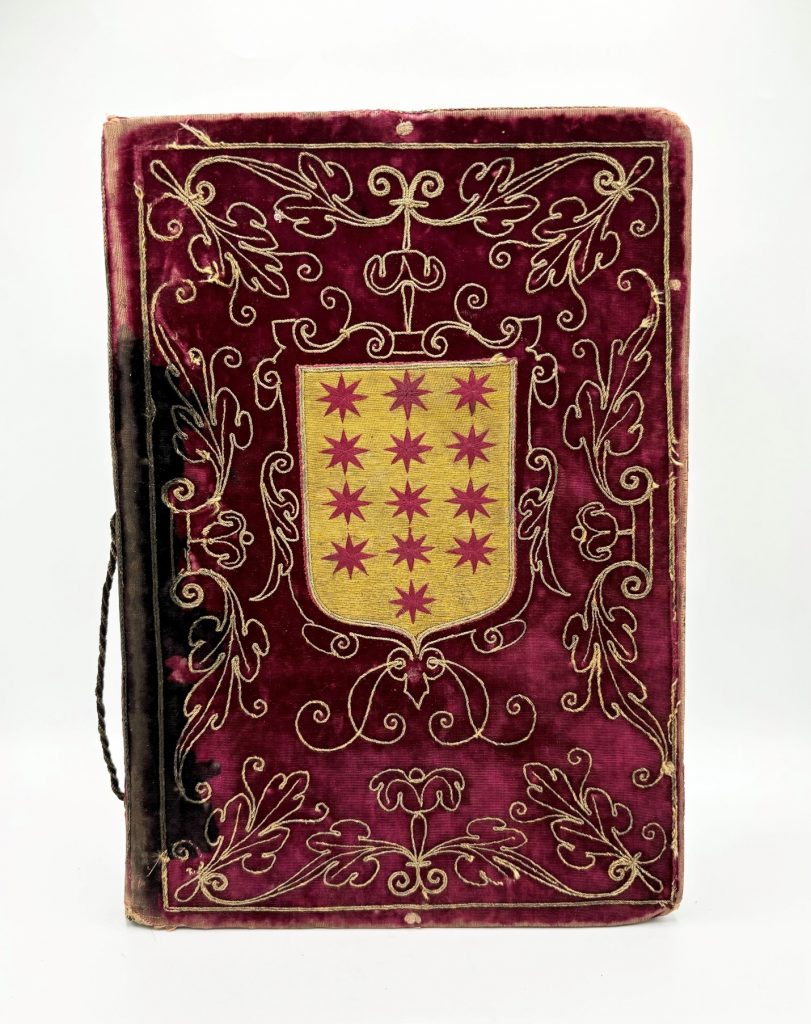

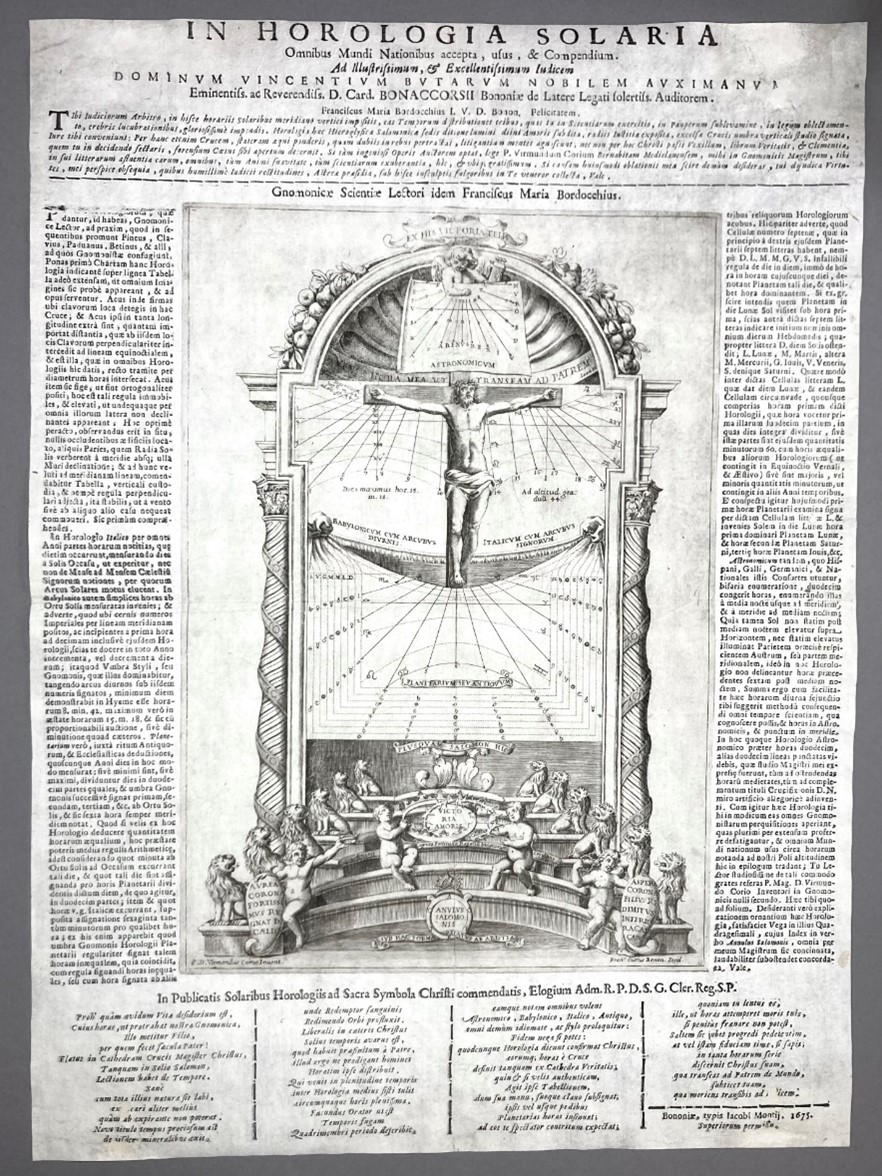

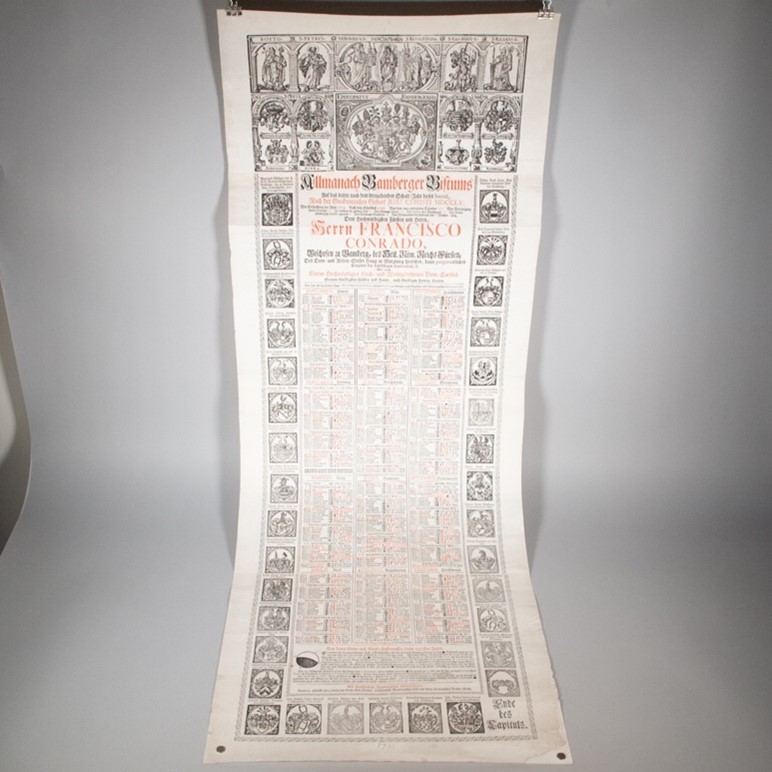

The illustrations depart from the more traditional seasonal and biblical scenes of earlier examples. Instead, the arms of the powerful Prince Bishop Franz Konrad von Stadion und Thannhausen are centered at the top.

The illustrations depart from the more traditional seasonal and biblical scenes of earlier examples. Instead, the arms of the powerful Prince Bishop Franz Konrad von Stadion und Thannhausen are centered at the top.